Leadership Conference Held at VMI

Jan Rader shares how the city of Huntington, West Virginia battled drug trafficking. -VMI Photo by H. Lockwood McLaughlin.

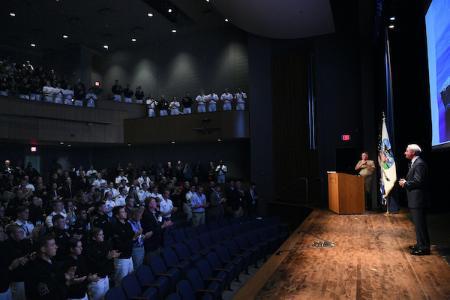

LEXINGTON, Va. Nov. 6, 2023 — The 14th annual Leadership and Ethics Conference at Virginia Military Institute was held Oct. 30-31 in Marshall Hall. This year’s theme was “Leading During Crisis: Culture, Conflict, Collaboration,” and attracted students from across the country. The conference focused on the challenges of adapting to personal and organizational crises with courage and integrity as an individual and as a leader.

Nearly 200 participants, with students from many colleges, universities, and military academies from across the nation including Christopher Newport University, East Tennessee State University, Hampden-Sydney College, Liberty University, Mary Baldwin University, Norwich University, Texas A&M University, The Citadel, U.S. Coast Guard Academy, U.S. Military Academy, University of North Georgia, Virginia Tech, as well as many VMI cadets, gathered to hear inspirational speakers, participate in collaborative activities, and to network. Central to the conference’s programming were small group discussions and speakers focusing on crisis leader self-assessment, behavioral adaptability, crisis preparation, communication planning and execution, and building effective teams.

Maj. Gen. Cedric T. Wins ’85, VMI superintendent, welcomed attendees on Monday morning and challenged them to learn how leaders and their followers can build strong teams that anticipate and prepare for the complexity of crises of any kind, whether man-made, natural, or even slowly evolving ones. “Over the next two days, you will learn about yourselves, and how to examine crisis leadership through culture, preparedness, and response," Wins said.

The speaker kicking off the conference was the H.B. Johnson Jr., Class of 1926 Distinguished Speaker, Eric McNulty, associate director of the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative at Harvard University. McNulty is an expert in leadership, crisis management, and negotiation, and co-author of numerous books, including “You’re It: Crisis, Change, and How to Lead When it Matters Most” and author of “Three Critical Shifts in Thinking for the Evolving Leader” and “Your Critical First 10 Days as a Leader.”

McNulty opened by declaring the world is currently in interesting times - which is a curse. “We have a war in Europe, the Middle East is on fire, the U.S. has set yet another record for billion dollar-plus disasters resulting from natural hazards, and we’ve got political polarization.” He stated that throughout history there are periods of relative calm, instability, and prosperity, and he believes the world is moving toward a time of more disruption. He counseled the students in the audience, that whether they serve in the military or work in the civilian world, they will face a much greater set of disruptions, and as such must master the dimensions of meta leadership.

Meta leadership as McNulty defined it, is being able to look at the big picture, and take in the broader view. He stated there are three dimensions of meta leadership: the person, the situation, and connectivity. In explaining the first dimension he said, “We are all different and lead differently, so you need to understand who you are as a leader, be comfortable with yourself, and know your strengths and weaknesses.” He described great leaders as having character, integrity, and being trustworthy. They listen well and care for others, and invest in the mission and the success of others. He shared a graphic of what he called the “Double Helix of Self” with his polished side of self on one side of the helix, where he listed his accomplishments and achievements, and on the other side he listed parts of his life that were disappointments and heartbreaks. “When you lead, embrace both sides of your helix. That’s where your strength comes from, it’s who you are, and gives you empathy. Pretending you have no vulnerabilities, makes you more vulnerable,” he shared.

In explaining the second dimension of meta leadership — the situation — McNulty introduced a diagram called the “Pop-Doc Loop,” a continuous process model that flows through six cognitive properties: perceive (seek verifiable evidence, get input from others), orient (look for patterns, discern order from chaos), predict (understand possible future challenges, forecast possible outcomes), decide (make decisions, act), operationalize (What’s needed to carry out the decision? What role will partners play?), communicate (provide routine updates, work to understand consequences) and back again to perceive. He explained that the model assumes leaders are not perfect, and it is designed to allow for updates, corrections, and improvements.

Connectivity, the third dimension of meta leadership, is about bringing people together in unity of purpose and actions. “Leading is all about trust-based relationships. Keep your emotions and ego under control. Train your people to do their jobs well, and to work together,” he advised.

McNulty closed by reminding his listeners of what’s not at stake in dealing with stressful crises. “When I go home at the end of the day, my dog is always there wagging his tail to greet me. He doesn’t care if I had a great day or a lousy day, he is just happy to see me. Your family and friends will always be there to love and support you. That is what is truly important.”

VMI alumnus Kevin Black ’99, veteran U.S. Army officer, executive coach, and strategic advisor, spoke on “Behavioral Adaptability.” He opened by asking his audience, “What is the primary driver for a crisis?” After a few responses, Black boldly declared, “It’s humans. Think about COVID. The reaction to COVID was worse than COVID itself. Why is the reaction to a crisis always worse than the crisis? Because of human complexity and personality.”

To illustrate his point, Black displayed a picture of a multi-layer cake, and listed examples of layers of a human personality. “Perception, culture, environment, ego, life experiences, religion, philosophy, worldview, psychology, all these factors affect how a person reacts to chaos.” He continued by noting there are two fundamental orientations to leadership: mission-oriented leaders who are focused on the goal and want to win at all costs, and people-oriented leaders, who are focused on engaging with people and gaining trust through relationships. Every leader has a behavioral profile that leans one way or the other, often changing in a seesaw fashion, depending on the situation.

Black concluded by stating that everyone is unique and comes to their leadership roles with their own perspectives. “If we were all tasked with writing a book about sharks, no two books would be the same. Remember that as a leader. The people you lead will all be different, and as a leader, you must be mindful of that with your leadership style.”

Jan Rader, retired fire chief for the city of Huntington, West Virginia, and first woman to reach the rank of chief for a career department in the state of West Virginia was the Caroline Dawn Wortham ’12 Leadership Speaker. Rader came to national prominence after the release of the short documentary “Heroin(e)” by Netflix in September 2017. Then in April of 2018, she was chosen as one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world. She currently serves as director of the Mayor’s Council of Public Health and Drug Control Policy in Huntington.

Rader shared Huntington’s history of dealing with the evolving illegal drug trade throughout her career: The pill mill epidemic when a population of their people had become addicted to pain pills; the heroine problem and addicts reusing dirty needles; then the deadly trade of fentanyl and methamphetamines. “When I started with our fire department we would ride out on emergency calls, do our tasks, put out fires, then all of a sudden we're being called out for overdoses. We wondered what was going on. We didn't understand the big picture that life was changing on our streets,” she shared. It was at that point she knew she wanted to affect change in drug trafficking in Huntington.

When Mayor Steve Williams was first elected in 2013, he accompanied the police on many drug raids and witnessed overdoses firsthand. As a result, the city started a program called “River to Jail.” “If a dealer came across the Ohio River into Huntington to sell drugs, they were going to go to jail. Within three months there were 226 arrests, but within two weeks you couldn't tell any arrests have been made. That's how many people were waiting in the wings for their opportunity to sell drugs,” recalled Rader. It was at that point they changed their strategy and started to work on the demand side of drug trafficking in addition to the supply side, and the mayor began an Office of Drug Control Policy.

Knowing that Rader was also a nurse, the mayor asked her to become a member of the new agency in addition to her fire chief duties. “It was me and two others. We traveled 45 minutes from Huntington to visit a Harm Reduction Program. We observed how people were responding to getting clean syringes, wraparound services, referrals to treatment, and help with life in general to make themselves better. Clearly the program was a success. We decided we had to do this for our people, and that was the beginning of the path we went down,” she reported.

The office began to keep real time data on tracking overdoses, as well as educating people in the community. “We met with small groups, no more than 10, and we started with the faith community who welcomed us with open arms. We discovered that faith leaders were struggling with helping members of their congregation, and they wanted help from us. We built a program called ‘Faith Community United’ to help educate faith leaders on how they could help their members,” Rader said. The comprehensive program saw positive results with the number of overdoses and deaths due to overdose gradually decreasing each year.

Another problem Rader encountered was compassion fatigue among the first responders. “A fire department goes through a lot of wear and tear on their equipment which costs a lot of money, but you can't measure the cost associated with the wear and tear on your people. By looking at our basic data, we calculated that the average firefighter in Huntington in 2017 saw five deaths a month. So we started a wellness program called Compass that is for first responders and run by first responders. They decide what they want, and what they need. I consider it a huge success,” she stated.

Rader ended by telling her audience that communication is key. “You must have good communication skills, listen to your people, and validate what they are experiencing. You must be flexible, and not afraid to fail. Because I've learned a lot more from my failures than I ever did from my successes. Be compassionate, it changes the way you lead when you open your heart and see how everybody else lives.”

Two alumni speakers, Bob Foresman ’83 and Miguel Monteverde ’66 shared practical advice and personal anecdotes in smaller breakout sessions. Foresman has had a career in emergency management and preparedness, and Monteverde had a long career, both in the military and as a civilian, in media relations and crisis communications.

The second day opened with a moderated panel discussion with law enforcement professionals discussing crisis situations they responded to as leaders. Retired Fairfax County Police Chief Robert Beach shared the complexity of being the incident commander for the county on 9/11 when the plane hit the Pentagon. Milton Franklin Jr., police chief of Bridgewater College, discussed the 2022 shooting at the college that killed two officers on his force. VMI Police Chief Mike Marshall spoke of the time he was incident commander while working for the University of Virginia police department, and a credible bomb threat was made during the 2005 Rolling Stones concert in Charlottesville. All panel members stressed the importance of preparation and constant training.

VMI adjunct professor Dr. Stephen Lowe presented an in-depth case study workshop on the Mann Gulch forest fire in 1949. The interactive session had attendees apply the knowledge gained from earlier speakers to analyze the preparedness, leadership, followership, and communication aspects of the tragedy, in which 12 U.S. Forest Service smokejumpers died. He was joined by former Hotshot smokejumper and current Lexington resident, Christian Duncan.

Lippold relayed his story of what is considered to be one of the most brazen acts of terrorism by al Qaeda prior to 9/11. The large audience was comprised mostly of students who were born well after the ominous event. Lippold’s rapid-fire recitation kept listeners hanging on to his every word, and his attention to detail allowed them to visualize themselves on the deck of the ship on that fateful day.

When Lippold originally took command of USS Cole, he had one year to get the ship ready for deployment. He made sure his crew were all painstakingly well-trained for their specific jobs, so they could respond automatically under a crisis. “They weren’t happy about the intense training I put them through at the time, but two months later when we got hit, they had the competence to know if someone was missing from their station, and the confidence to step up into those now vacant positions. They were able to do what was necessary to save our ship and save our shipmates,” Lippold stated proudly.

USS Cole was first deployed to the coast of the former Republic of Yugoslavia to provide support for fourteen days, then on to the Middle East. Because they had been held back for two weeks, in order to reach their destination in time, they had to race across the Mediterranean and down the Red Sea at double the normal speed and burned a lot of gas. They pulled into the port city of Aden, Yemen, for a routine fueling stop. Lippold relayed what happened as his ship was taking on fuel, “As I'm sitting at my desk at 11:18 in the morning, there was a thunderous explosion. You could feel all 505 feet and 8,400 tons of guided missile destroyer suddenly and violently thrust up and to the right. The ship seemed to hang for a split second before it slipped back down into the water, and rocked from side to side. Power failed, lights went out, ceiling tiles popped out, and a table that had coffee and water on it flipped over. I came up on the balls of my feet and grabbed the underside of my desk in the brace position as everything popped up and slammed back down.”

A small bomb-laden boat, had pulled alongside and detonated explosives ripping a 40-foot-wide hole in the ship, killing 17 and injuring 39 crew members.

Not knowing if the ship would be boarded or if there would be a follow-up attack, Lippold grabbed his personal weapon, loaded it, and left his cabin to survey the damage. “I took that deep breath and said ‘Well this might be your destiny. If you see someone that doesn't belong, duck first and don't leave any round in the chamber,’” he recalled. Thankfully the terrorists died in the attack, and Lippold did not have to use his weapon.

He discovered that the uninjured members of his crew had taken it upon themselves to set up a triage center for the injured, provide damage control of the ship, and conduct security watches to make sure no other attacks would occur.

Lippold’s priority was to save the ship. He paused his narrative to advise the audience on making decisions during a crisis. “You start making decisions based on the best information you have at that moment. As time moves forward and you get better information, and you need to change the decision - change it! Even if it means you have to do a 180-degree change. That's one of the things that has to constantly happen during a crisis. Don't get locked-in and feel you've got to stick with the previous decision.”

Lippold contacted the Yemeni Port Authority by radio and asked them for three things to which they readily agreed: freeze all harbor rules, notify local hospitals, and maintain open communication with them. The Yemenis said they would send boats out to get the wounded off and take them to the hospitals, Lippold agreed but warned them, “You must not come any closer than 100 meters to my port side or I will shoot you." The Yemenis said they understood and when the boats started coming out, Lippold observed a very unique phenomenon, “I don't care where you are in the world, when you tell someone something like that, there is no problem with the English language. Most boats made a huge 300-meter arc around the stern of the ship. We had to get used to boats coming out to us that didn’t represent a threat. By the same token the Yemenis had to get used to a very angry, very agitated crew that had broken out every weapon that were locked, loaded, and safeties off: Machine guns, grenade launchers, shotguns, pistols, wrenches, hammers, screwdrivers,” he quipped. Then very seriously said, “Whatever it was going to take to defend the ship, we were ready to do it.”

At the end of 17 days, the crew had saved their ship, their shipmates, and got the USS Cole underway out of the harbor, and toward the coast, where it would be loaded unto the heavy lift vessel, Blue Marlin. “As we got towed out by the tug, what did that really signify for us? It was that ability to bounce back. It's that resiliency to get through a major event like this not only to survive, but excel at it. I turned to my executive officer at that moment and told him to play the first song on the PA system, the ‘Star Spangled Banner.’ I wanted our national anthem echoing across the harbor to send a signal to the Yemeni people that despite what had happened to us, we were leaving with our heads held high. I turned to my executive officer again and said, ‘play the second song.’ It was the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ again, but this time it was Jimi Hendrix’s rendition.”

The USS Cole was repaired in Pascagoula, Mississippi, over a period of two years, and returned to the fleet. It remains an important warship among the surface forces in the Atlantic.

Next year’s Leadership Conference will be held on Oct. 28 – Oct. 29, 2024, with an announcement of the theme and title coming in the spring. To stay informed, visit the conference website and join the mailing list at conferences.vmi.edu/leadership.

Marianne Hause

Photos H. Lockwood McLaughlin

Communications & Marketing

VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE

.svg)

.png)