Toilet Paper Shortage Illustrates Economic Theory

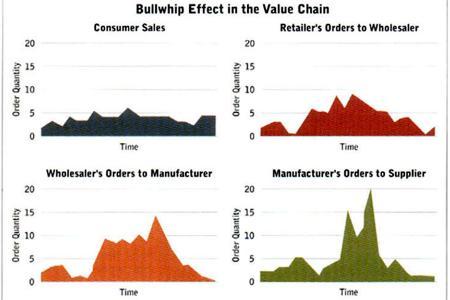

A diagram of the bullwhip effect. - Photo courtesy of Col. Barry Cobb

LEXINGTON, Va., April 23, 2020—Each spring, Col. Barry Cobb teaches supply chain management—how products go from raw materials into the hands of consumers—in his operations management class. This year, the toilet paper shortage engendered by the coronavirus pandemic provided him with a real-world example of a supply chain issue that’s affected nearly every American.

Specifically, the sudden surge in demand for toilet paper—a product that normally doesn’t see spikes in demand—has created what’s called a bullwhip effect.

“The bullwhip effect occurs when a change in consumer demand that is either a small or temporary change is amplified as orders move back through the supply chain to the manufacturer,” explained Cobb, who holds the Roberts Free Enterprise Chair in the economics and business department.

It takes time, of course, to work out the kinks—and because toilet paper, like most consumer staples, is produced with a lean supply chain, there are not millions of extra rolls just sitting in warehouses. And because the demand for toilet paper will eventually return to a normal level as people realize they aren’t going to be quarantined forever, there’s little incentive for companies to build new toilet paper factories.

“For [manufacturers] to add extra capacity wouldn’t be advantageous,” said Cobb.

Bigger retailers, though, have the advantage when it comes to working through a tangled supply chain, as they have more leveraging power. “Sam’s Club was re-stocked before a lot of retailers because of Walmart network’s ability to shift shipments to different routes,” Cobb wrote in an email.

Cadets, meanwhile, have gotten to learn about supply chains from both a theoretical and practical standpoint.

“Being in operations management during the coronavirus pandemic takes applied learning to a whole new level,” wrote Owen Carney ’20 in an email. “Instead of simply working through fictional examples about supply chain issues, we get to see how those issues present themselves in the real world.”

Carney has also learned what needs to happen once the bullwhip effect takes hold. “To reverse the bullwhip effect, we learn that supply chains must increase the availability of information, improve forecast accuracy, and eliminate order-batching, which is when retailers accumulate too many or too few products without considering the demand for them,” he wrote.

Jonathan Hutson ’21 noted that in a crisis, normal business operations can be turned upside down so quickly that companies have little time to react. “Operations management has shown that the way stores normally operate is based on data from ‘normal’ circumstances,” he wrote in an email. “When a pandemic strikes, this data has to be adjusted to account for the surges in demand.”

Thanks to the pandemic, Cobb has been able to take economics, a subject often dependent on theoretical examples, and find a multitude of real-world examples that illustrate the theory.

“Any concept you are trying to teach is taught better when you relate it to a real-world example,” he commented. He added that nearly all of the cadets are seeing supply chain disruptions for the first time in their lives—and in economics, where games and game theory play a central role, this spring has brought a jump from the theoretical to the practical.

“Now, [cadets are] seeing the game right in front of them,” said Cobb.

- By Mary Price

-VMI-

.svg)

.png)