Post-Civil War

ERH-411, Spring 2022

Research conducted by Emma Faust ’23 and Jonathan Ballesteros ’24 under the guidance of Lt. Col. Pennie Ticen and Maj. Jeff Kozak.

The post-Civil War period was known as the Reconstruction era within American history. During the war, the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) played an important strategic role because of its geography. 257 members of VMI’s Corps of Cadets marched into the Battle of New Market, serving as reinforcements for General John C. Breckinridge’s Confederate Army. Ten cadets were killed during this battle.

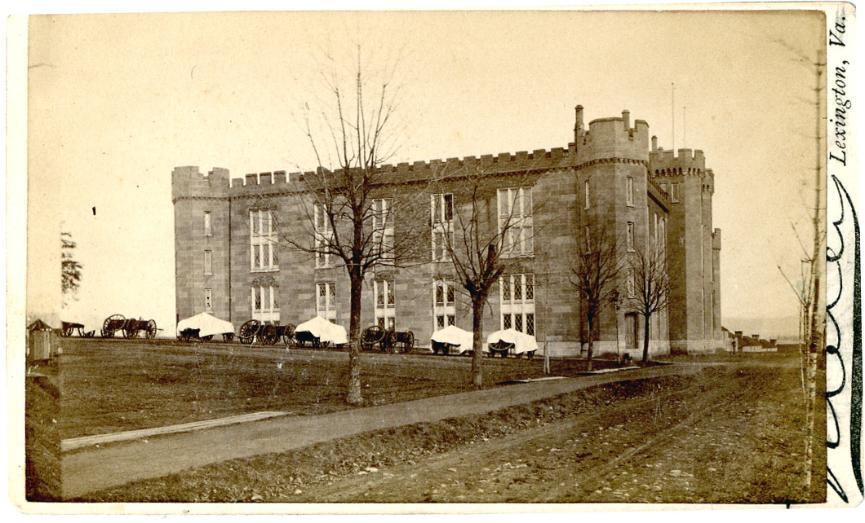

Following the Battle of New Market, in June of 1864, Major General David Hunter ordered his army of 1,800 Union troops to march into Lexington to destroy Post in retaliation for VMI’s participation in the battle. Among other buildings, VMI’s barracks was heavily damaged.

Following the war, as the Institute was rebuilt, many people saw this as an opportunity for change to some of VMI’s culture and traditions.

Brief Overview & Budget

The Virginia Military Institute (VMI) was reopened in the Fall of 1866, initially with only 18 cadets. The lack of communication through the postal system meant that many cadets did not receive word of the Institute's reopening until later in the fall, so more cadets returned in December. Upon their return, many of the cadets had to temporarily live in Lexington because there was no place to live while Barracks was being reconstructed.

Following Hunter’s Raid on VMI, Francis H. Smith, the Superintendent at the time, created a plan for reconstruction. As part of his plan, he replaced the faculty, negotiated with Virginia’s State Legislature, and relocated the Corps of Cadets into town while the Institute was being rebuilt. During this time, he reached out to West Point for help, but their Superintendent rejected his request because of the Institute’s connection with the Confederacy. For this reason, he then spoke with VMI’s Board of Visitors and asked for their permission to propose an assistance program for VMI with Virginia’s legislators. In addition, a large portion of the money that was used to rebuild came from a civil lawsuit that VMI filed against the U.S. because of its destruction by Union troops.

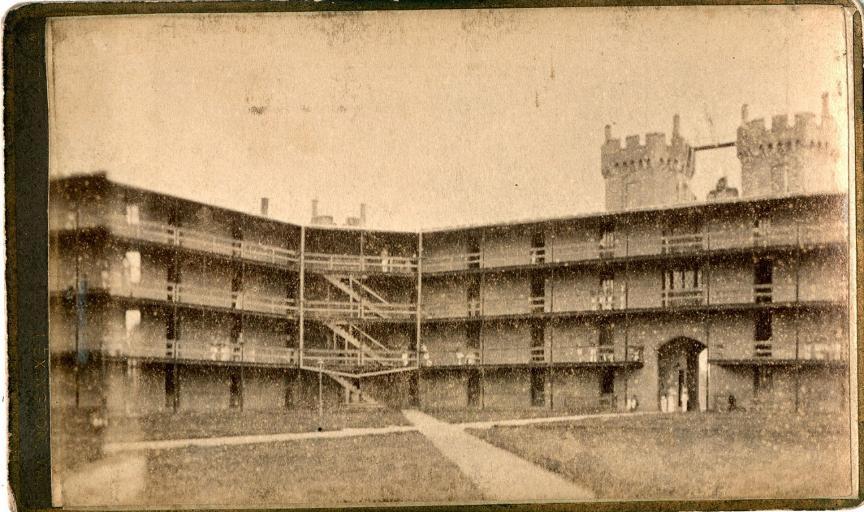

Barracks courtyard, ca. 1880. Part of the VMI Archives Photographs Collection.

Barracks East Wing 1876. Image from Cadet Photograph Album, 1876-1880, Part of the VMI Archives Photographs Collection.

Washington Statue

During Hunter’s Raid, the Union troops stole the statue of George Washington, which had been present on Post since 1856, as a trophy. Due to their poor method of transportation, they were unable to make it past West Virginia because of the statue’s weight. After the Civil War, the statue was returned to Lexington and rededicated in the Fall of 1866. On its way back, it was transported by the National Express Company and Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company. It was first dropped off in Lynchburg, Virginia and then finally relocated to Lexington by JR Echols.

Cadet Cemetery

During the war, 10 cadets lost their lives. Due to the financial constraints on VMI as it struggled to rebuild after the war the remains of the 5 cadets that were returned to VMI for burial were kept in the Ordinance Sergeant's quarters. The cadets were initially interred in the Cadet Cemetery in 1878, near the northwest corner of the Parade Ground. In 1912 they were moved to the statue of Virginia Mourning Her Dead, which had been relocated to its present location behind which Nichols Engineering Building was built in the 1930s.

Samuel Lawrason, VMI Cadet, ca. 1872. Part of the VMI Archives Photographs Collection.

Timeline

The popular method of communication during this time was through letters. The photo album, A Virginia Military Institute Album, 1839-1910 by Diane Jacob and Judith Arnold, provides excerpts from Cadet Edwar Minor Watson’s letters to his father during 1868. In these letters, he would describe a cadet’s daily routine; A way of life that has not been changed throughout the Virginia Military Institute’s history.

0500 (5:00 AM) - “At 5 o’clock…I was awakened by the most dreadful noise. I at first thought that the house was falling or that a volcano had burst in about a quarter of a mile from where I hardly knew, as I found myself lying with nothing between me and the floor except a mattress about three feet wide. I was soon enlightened as to the cause of the disturbance, by an old cadet, who in the dim light of the very early morning, as he stood dressed close by, I had not noticed. He remarked in a tone which seemed anything but motherly, ‘Rat get UP Sir, and go to reveille.’ At this I opened my eyes somewhat wider, and remembering the state of affairs I thought it best to as he said.”

0530 (5:30 AM) - “We were then disbanded and were given ½ hour to make our toilets and clean up our room. In cleaning up our room we have to take everything from the tables and chairs and put them in their proper place and have to roll up our beds in a bundle…At the end of the half hour the inspectors visit.”

1400 (2:00 PM) - “The drum calls us to study. We recite until 1 o’clock when time is given for dinner…At 2 o’clock we are again called to study. At 4 o’clock we are dismissed.”

1630 (4:30 PM) - “At 4 ½ we are called for evening drills. The drill lasts 1 ½ hours. We then have 15 minutes to fix the dress parade. After the parade, 5 minutes is given to change clothes.”

1815 (6:15 PM) - “We then march to supper…Each one having reached the seat assigned assumes the position of a soldier and stares at the boy on the opposite side of the table in the face (who by the way in my case is mighty ugly). We have to wait until everybody has found his place. Then at the word ‘be seated’ each head of the three hundred cadets bobs down and we commence eating.”

Commentary from Cadet Edmund Berkeley to his mother on the Mess Hall’s breakfast, November 26, 1863:

“Today for breakfast we had only two pieces of bread and about a half gill of milk with what we call growly which is made of mutton beef feet or any other thing they can make for dinner. We have beef and cabbage or turnips one day and beef steak and soup the next. We have nothing that I would have eaten at home but I am so hungry when I go to meals that I think even turnips are delicious, but I live off of it very well…Everyone says I have fattened very much.”

1845 (6:45 PM) - “We have then 15 minutes, when we are called to study. We study until half past nine when we are called to tattoo. Then in five minutes the drum sounds for blowing out lights.”

(“Tattoo” is another word for TAPS, which is played in Barracks at the end of the day as a signal for cadets to turn off their lights. TAPS is also played by the military as a remembrance for those soldiers who have made the ultimate sacrifice by giving their lives in service to their country.)

2130 (9:30 PM) - “The Inspector visits immediately to see that everybody is in bed and then nothing is heard but the tread or challenge of the sentinel until five in the morning.”

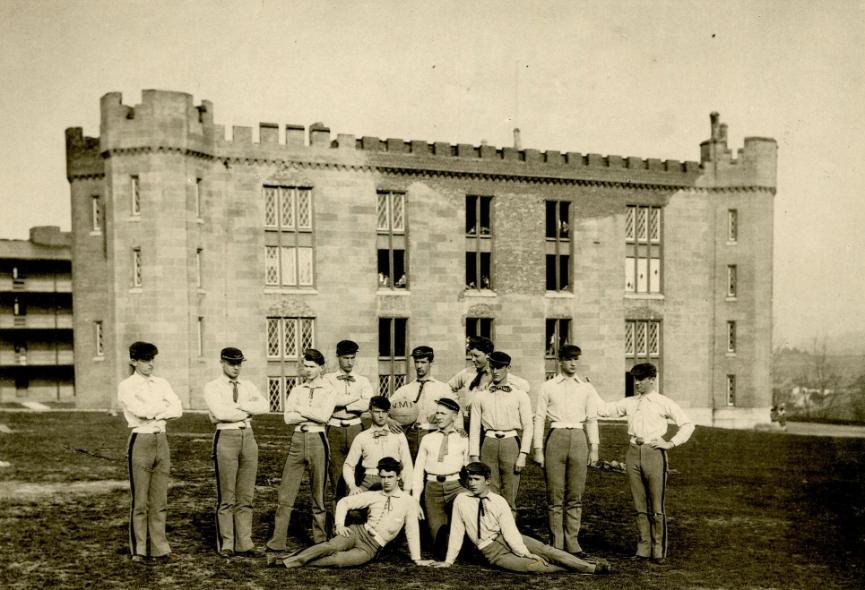

Athletics

Football Team in Front of Barracks 1884 . Players are: Thomas W. Lackland, George W. Fitchett, Gideon B. Miller, John H. Winston, Hugh G. Meem, Gaillard S. Fitzsimons, William H. Palmer, Greenlee D. Letcher, Robert L. Wilson, William H. Palmer, Edward L. Darst, Thomas J. Nottingham, William A. Irvine. Part of the VMI Archives Photographs Collection.

The first sport at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) was football and it was established in 1885. During this time, football was not as regulated as it is now. It was a mixture of rugby and soccer and the size of a team was determined by the number of players present. The size of the field was also determined by both teams. The first football coach arrived in 1895, ten years after football was introduced at VMI. The second sport at VMI was baseball and it was established in the Fall of 1886. The game was played on the parade ground and during its first season the team played 23 games: 20 wins, 1 loss, and 2 ties.

During Virginia Military Institute’s (VMI) reconstruction, many of its faculty were replaced because they did not return. However those who did come back, they came back at a price. In an effort to reduce expenditure, each professor’s yearly salary was roughly $1,800. A professor’s first year would be paid $400, after reconstruction this salary would be increased to $900.

Faculty group 1892-93 with Superintendent Scott Shipp. Part of the VMI Archives Photographs Collection.

John Mercer Brooke

Colonel John Mercer Brooke taught at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) from 1865-1906. Before he taught at the Institute, Brooke graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1847 and was a navigator for the USS Powhatan. During the 1850s, he invented the precursor to the sonar system. When the South seceded from the North, Brooke resigned his commission and joined the Confederate Navy in 1861. He was instrumental in the use of armor plating on naval ships, and he was promoted to Commander in 1862. His great grandson and great-great grandson are members of VMI’s faculty today.

Matthew Fontaine Maury

Matthew Fontaine Maury also known as the “Pathfinder of the Seas” joined the Virginia Military Institute’s (VMI) faculty in 1868. As an important figure in naval history, he brought his research to VMI and taught Physics until his death in 1873. Maury joined the Navy in 1825 and resigned in 1839 because of a stagecoach accident. However, that did not stop him from changing the way that ships navigate while out at sea. While in-charge of the U.S. Naval Observatory and Hydrographic Office, he began to map out different maritime winds and currents which are still used today. During the Civil War, Maury joined the Confederate Navy and invented the first naval mine. After his death in 1873, his remains were left in an open casket in the VMI’s library before being buried at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Field of Studies & Transcript

Cadets are ranked based on their progress in each course. The numbers underneath their courses signify what subjects the Cadets excel in and what subjects Cadets do not excel in, and with that they are ranked.

-865x585.jpg)

1875 First Class Register, part of the VMI Archives. 1875 Register PDF Version.

As a result of the rigors of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), many cadets during this time found themselves using anything at their disposal to have fun. However, some of these past times were often costly and mischievous. A secret society that came out during this time were the Molly Maguires. As a result of the Civil War, many cadets had access to weapons and explosives because of the fear of another attack by the North. This group engaged in setting off small black powdered bombs in the Barracks courtyard for entertainment. However by the 1900s, this organization was banned and looked down upon by the Corps because of its dangerous nature. Although they were banned, the tradition of screaming “bomb in the courtyard” survived after World War II.

Members of the secret society, the Molly Maguires at VMI, circa 1890. Includes Frank G. Doggett, Class of 1892; John B. Nicholson, Class of 1893. Part of the VMI Archives Photographs Collection.

Full-size images with zoom capabilities can be viewed by either clicking on the image within the expanding panels or on the link in its citation.

.svg)

.png)