Stonewall Jackson at VMI

The VMI Museum is a major repository of artifacts relating the life of one of America’s revered Civil War generals, Thomas J. Jackson. His favorite hat, two uniforms, items from his classroom and even his war horse, "Little Sorrel" can be seen in the museum.

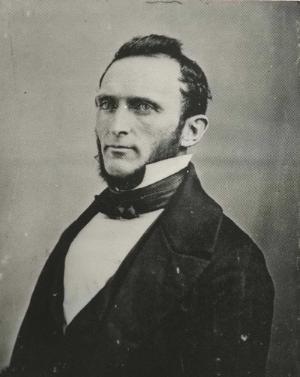

Born on January 21, 1824, in Clarksburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), Jackson was orphaned as a young child. He had little formal education. This did not stop him from seeking an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Upon his graduation on July 1, 1846, Jackson was commissioned as a second lieutenant of artillery, and he entered the fighting in Mexico. By the end of the war, Jackson had been promoted twice, holding the rank of Brevet Major.

Born on January 21, 1824, in Clarksburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), Jackson was orphaned as a young child. He had little formal education. This did not stop him from seeking an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Upon his graduation on July 1, 1846, Jackson was commissioned as a second lieutenant of artillery, and he entered the fighting in Mexico. By the end of the war, Jackson had been promoted twice, holding the rank of Brevet Major.

In 1848 new, specially made cannon arrived at VMI. They were 300 pounds lighter than regular guns and painted red! Jackson trained

cadets with these cannons.

In 1851, the VMI Board of Visitors was seeking a professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy (Physics) who could also teach artillery tactics. In February the superintendent of VMI offered Jackson the position at the Institute, which he accepted. A marginal professor of natural philosophy, Jackson proved to be an excellent instructor of artillery. Using the Cadet Battery ), six cannons made especially for VMI, Jackson ruled the parade ground. The cannon can still be seen at VMI today. He was a strict taskmaster, with unbending integrity and fearlessness in the discharge of duty. The major was described as being "as exact as a multiplication table and as full of things military as an arsenal."

Professor Jackson wore this blue uniform at VMI and at the Battle of Manassas. The coat was recently restored with the grateful support of the Virginia Division of the UDC.

If Jackson was exacting in the demands he made upon the cadets, he was no less so in the demands he made upon himself. At VMI, Jackson taught his classes with the same directness with which he thought. He never wavered in his character, his devoutness to church, his dependability, faith, and resolution. These qualities overshadowed any professorial deficiencies and set a standard that even his young cadets recognized as one of greatness.

Jackson would become an active business and religious figure in the Lexington community, Finding religious direction from George Junkin, a noted Presbyterian minister who was president of Washington College, he became a member of the Presbyterian Church. During visits at the Junkin household, he fell in love with the youngest daughter Ellie. They were married after a quiet courtship, and they established their life in the Junkin household. It was the happiest time that Jackson had known until then. This happiness was to be short-lived when Ellie died during the birth of their first child. Jackson was profoundly grieved and recovered slowly. After a trip to Europe in 1856, he returned home and proposed marriage to Mary Anna Morrison, the daughter of another Presbyterian minister who also happened to be president of a college (Davidson). Thomas and Mary Anna purchased a home on Washington Street, the only home he would ever own, and they became the idealized Victorian couple.

In 1859 VMI cadets had an indication of what was to come with the abolitionist John Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry. Brown was captured by a detachment of U.S. Marines under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee, USA. At his trial, he was found guilty of conspiring to commit treason and was sentenced to be hanged. With fear of another uprising to aid Brown’s escape, the Governor of Virginia sought the aid of the VMI cadets to provide additional military presence. On November 25, 1859, Jackson moved a contingent of cadets to Harper's Ferry where they helped maintain order during Brown's execution on December 2.

"Little Sorrel" is one of two Civil War Horses to be mounted at death. He died in 1886.

In early April 1861, the unrest among the people of Lexington provoked several incidents, one of which resulted in one of Jackson' s few public speeches. One Saturday afternoon attempts were made to raise two flags in Lexington, one for secession and one for remaining in the Union. Lexington had strong Unionist feelings, many of the settlers of the area having come from Pennsylvania. The cadet corps tended toward a strong secessionist sentiment, as many of the cadets were from Tidewater Virginia. Many of them were in the town, as they had been released from duty. Excitement increased when a somewhat violent man drew a revolver and knife upon a squad of cadets, and though onlookers who intervened quelled the difficulty, word quickly spread back to VMI that a group of cadets was in danger. At the barracks, the already-aroused cadets grabbed their guns and began to run toward town. The superintendent headed them off and ordered them to return to barracks. There the corps was assembled, and the superintendent urged Jackson to speak to the cadets. "Military men make short speeches," he said, "and as for myself, I am no hand at speaking anyhow. The time for war has not yet come, but it will come and that soon; and when it does come, my advice is to draw the sword and throw away the scabbard."

With the outbreak of hostilities, the cadets were ordered to Richmond to serve as drill instructors for Confederate recruits. Under Jackson's command, the cadets left VMI on April 21, 1861, and reported to Confederate headquarters at Camp Lee. There Jackson was commissioned a colonel in the Confederacy and, leaving his cadets at Camp Lee, moved on to active military service with the Southern forces.

Jackson was wearing this raincoat when he was wounded by his own men.

From Manassas (1861) to Chancellorsville (1863), where he was fatally wounded, Lieutenant General Jackson was unequaled on the battlefield. Using his knowledge of the Shenandoah Valley, he baffled his opponents. His tactics of quick movement and stealth are still studied today by military leaders from around the world. Jackson's accidental wounding by his own troops at Chancellorsville occurred on the night of May 2, 1863, during the confusion of the hotly contested battle. His badly wounded left arm was amputated, but the general died of complications in the early hours of Sunday

morning, May 10.

Jackson's name was still carried on the VMI faculty roll at the time of his death, for he had expressed his intention of returning when the war was over. He was the first faculty member to die since VMI was founded in November 1839. His body was brought to Lexington by packet boat on the afternoon of May 14. The VMI Corps of Cadets met the boat and escorted the body of their former commander to VMI where it lay in state in his old classroom with cadets standing as guards. The cadet battery, which Jackson so long commanded, fired salutes from sunrise to sunset. One day later, Stonewall Jackson was buried in the Lexington cemetery that now bears his name.

.svg)

.png)